United States: The onset of COVID was abrupt, its spread unrelenting, claiming millions of lives globally in a brief yet catastrophic sweep.

Since that calamity, an undercurrent of unease persists regarding the potential emergence of another devastating infectious disease—whether viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic in nature.

With COVID now largely subdued due to the efficacy of widespread vaccination campaigns, public health officials have shifted their vigilance toward three significant adversaries: malaria (a parasitic menace), HIV (a viral foe), and tuberculosis (a bacterial threat). These three collectively account for an annual death toll nearing 2 million individuals, according to The Conversation.

Beyond these persistent killers, there lies an ever-evolving roster of priority pathogens—especially those that have developed resistance to conventional treatments such as antibiotics and antivirals.

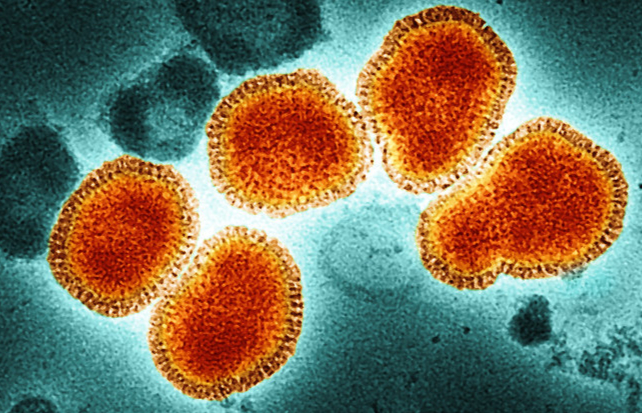

In parallel, researchers meticulously survey the landscape for emergent threats. Among potential candidates, influenza viruses stand out as particularly concerning due to their propensity for rapid outbreaks.

Currently, influenza A subtype H5N1, colloquially termed “bird flu,” is arousing significant alarm. This strain is widespread among avian species, both wild and domesticated, including poultry. Recent cases have also implicated dairy cattle in various US states and equines in Mongolia as hosts, as per The Conversation.

When influenza proliferates among animals, there is an inherent fear that it could leap to humans. Alarmingly, this fear is materializing, with 61 documented human cases in the US this year alone. Most instances are linked to farmworkers handling infected livestock or individuals consuming unpasteurized milk.

This figure marks a stark rise compared to only two cases in the Americas over the previous two years. Compounded by a staggering 30 percent mortality rate among human infections, bird flu is rapidly escalating as a priority for health authorities.

Fortunately, the current strain of H5N1 lacks efficient human-to-human transmissibility. Influenza viruses rely on sialic receptors on cell surfaces to gain entry and replicate. Strains adapted to humans exhibit a strong affinity for human sialic receptors, facilitating their spread. Conversely, bird-adapted strains like H5N1 exhibit poor compatibility with human receptors, hindering their transmissibility.

Nonetheless, recent research reveals that a singular genetic mutation in the H5N1 virus could enable human-to-human transmission, potentially catalyzing a pandemic.

Should this transformation occur, swift governmental intervention would be imperative. Pandemic preparedness strategies, such as those outlined by global health organizations, are already in place to counter such eventualities. For instance, the UK has procured 5 million doses of an H5 vaccine as a precautionary measure for the anticipated risks in 2025, according to reports by The Conversation.

Even without human transmission, H5N1 is poised to inflict greater damage on animal populations in the coming year. This scenario presents not only grave animal welfare concerns but also significant repercussions for food supply chains and economic stability.

Interconnected Realities

The concept of “One Health” underscores the inseparability of human, animal, and environmental health. Each domain influences and is influenced by the others, forming a symbiotic web of interdependence.

By addressing and mitigating diseases within our ecosystems and among animal populations, we can preemptively curtail their infiltration into human domains. Similarly, safeguarding human health reinforces the well-being of animals and the environment, as per The Conversation.

While this integrated approach is vital, it must not detract from addressing the enduring “slow pandemics” of malaria, HIV, tuberculosis, and similar pathogens. Striking a balance between combating these ongoing crises and preparing for unforeseen threats is a critical endeavor.