During the current time, it is hard to eat a healthy diet, and the odd-tasting oils were hyped as a fix-all. Eventually, it was believed that one such oil was believed to be a pack of vitamin punch.

In today’s lexicon, the mention of “cod liver oil” evokes a hazy nostalgia, a memory of a murky spoonful wielded by a stern nurse or perhaps a figure from a Dickensian novel. The phrase is almost synonymous with antiquated remedies, far removed from the practices of modern medicine, according to the reports by BBC News.

The therapeutic concoctions of the 18th and 19th centuries have largely faded into obscurity, relics of a bygone era. Opiates for infants, syrup of figs, and castor oil—once hailed as universal solutions—have been relegated to history. Even the once-ubiquitous brimstone and treacle, long abandoned, now seem a quaint curiosity.

Yet cod liver oil, unlike its contemporaries, persisted, outlasting the age of snake oils and dubious cures. Extracted by heating the livers of codfish, its potency lies in its rich concentrations of vitamins D and A. Before the formal discovery of vitamins, keen observers noted that children who consumed the oil were less prone to rickets, a debilitating bone disease linked to vitamin D deficiency. The correlation was clear, but the science took time to catch up, as per BBC News.

In 1919, the underlying cause of rickets—calcium and vitamin D deficiency—was uncovered, lending credence to the remedy’s efficacy. During the hardships of World War II, the British government distributed cod liver oil to children under five, ensuring their developing bodies would not succumb to the ravages of malnutrition. “Don’t forget Jimmy’s orange juice & cod liver oil!” declared wartime propaganda, emphasizing the importance of this nourishment.

For all its benefits, cod liver oil was hardly a palatable solution. Exposure to air would oxidize the oil, transforming it into a rancid, fishy liquid that many found repellent. However, in the damp, sun-starved climate of the United Kingdom, basking in sunlight—a natural source of vitamin D—was a luxury often unavailable, making cod liver oil indispensable. This issue persists today, with the Met Office forecasting winters that could become 30 percent wetter by 2070, further limiting sunlight exposure.

As a response, many nations turned to food fortification. In 1940, the UK began mandating the fortification of margarine with vitamin D. Soon, bread, milk, and breakfast cereals followed suit. Across the Atlantic, the United States has been fortifying milk with vitamin D since 1933, a practice that continues today with various other staple foods. Even Finland, in 2003, initiated its own voluntary fortification program, receiving near-universal participation from food manufacturers, as the experts claimed in BBC News.

However, the UK’s efforts encountered a significant setback. Cases of hypercalcemia, a condition where excess calcium accumulates in the bloodstream, leading to kidney stones and other complications, emerged shortly after fortification began. It was suspected that children were inadvertently overdosing on vitamin D, prompting a ban on fortification, with only margarine and infant formula exempt from the ruling.

Surprisingly, cod liver oil never reclaimed its former glory. By 2013, the UK ceased fortifying margarine, advocating for vitamin supplements instead, a suggestion that was largely ignored. As more sophisticated methods for testing vitamin D levels became available, a disconcerting truth was unveiled.

During the winter months, when sunlight is scarce, nearly 40 percent of UK children in certain age groups are deficient in vitamin D, with approximately 30 percent of adults similarly affected. Individuals with darker skin are particularly vulnerable, as noted by public health nutritionist Judith Buttriss, who emphasized the critical state of vitamin D levels in the UK’s South Asian population in an editorial for the Nutrition Bulletin.

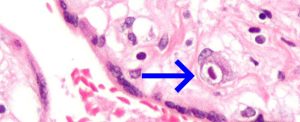

Alarmingly, rickets, once considered a relic of the past, are making a comeback. Hospitalizations for the condition, which had remained low through the 60s and 70s, began to rise in the 2000s. By 2011, scientists reported that rickets hospitalizations in England had reached their highest levels in five decades.

This resurgence has reignited the debate on whether fortification should be reinstated. The UK’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition is currently deliberating on the issue. It now appears that the hypercalcemia cases that halted fortification may have been caused by a genetic disorder affecting vitamin D metabolism, not by an overconsumption of fortified foods. Thus, the argument for reintroducing fortification gains strength.

While various factors likely contribute to the resurgence of rickets, it raises an intriguing question: Could the once-dreaded spoonful of cod liver oil once again become a fixture in households? The answer may lie in revisiting the wisdom of the past.